What Is Intellectual Property (IP) in the Context of Inventions?

What does intellectual property really mean when you are developing an invention? Intellectual property (IP) is often associated with patents, but in reality it is a much broader concept. IP refers to the legal rights that protect creations of the human mind, including technical inventions, creative works, designs, names, and other forms of commercially valuable knowledge.

People encounter intellectual property in many different roles. It may involve academic researchers, engineers in industrial R&D teams, lecturers working with students on applied research projects, or individuals developing ideas independently in their own time. In many cases, intellectual property is something that is assumed to be handled by an employer, a technology transfer office, or a legal department.

However, as soon as work leads to a concrete solution, prototype, or method that could be used outside its original context, intellectual property considerations come into play — often earlier than expected. At that point, decisions may already be made that affect ownership, publication, collaboration, or future use.

I should add that I encountered intellectual property in exactly the same way during my own research. At the time, it was not something I was particularly interested in. My focus was on doing good research, understanding the problem, and working towards the next publication. Questions about ownership, protection, or commercialization felt distant and largely irrelevant.

Only later did it become clear that intellectual property was already shaping what could and could not be done with the results — who could use them, who could publish, and under which conditions collaboration was possible. That realization did not come from an ambition to become an entrepreneur, but simply from seeing how the system interacts with research once it moves beyond the lab.

For inventors and entrepreneurs, intellectual property is not just a legal label — it is a strategic business decision. Different forms of IP serve different purposes, come with different costs, and fit different ways of making money from an invention. In some cases, formal protection such as a patent is essential. In others, copyright, design rights, trade secrets, or even speed to market may be the smarter choice.

This page introduces the conceptual framework of intellectual property in the context of inventions. Rather than explaining how to apply for specific rights, it focuses on why certain forms of IP may or may not make sense, depending on your business strategy. If you are looking for a practical, step-by-step explanation of the patent application process, that is covered separately on the page about how to get a patent.

Patents and Business Strategy

This website describes three main strategies for bringing an invention to market: Build to Sell, Sell an Idea, and Start, Grow and Scale. Each strategy, which are introduced on the homepage, places different demands on intellectual property, and patents play a different role depending on the stage of development, the business model, and the level of technical disclosure involved.

In many cases, patents become relevant once an idea has evolved into a clearly defined technical invention. Patent protection does not apply to abstract ideas, but to concrete technical solutions: how something works, how it is built, and how it differs from existing technology. For example, a general idea for a wireless phone charger must be translated into a specific technical concept before it can qualify for patent protection.

In some strategies — especially when you need to share an invention with external parties at an early stage — it can make sense to file a patent application sooner rather than later. This situation often arises in a sell an idea strategy, where early disclosure is necessary to explore partnerships, funding, or licensing opportunities. In such cases, a provisional filing or an early patent application can help establish ownership and priority before further development takes place. This is typically the moment when inventors begin to ask whether an idea can be patented at all, and how early protection fits into their overall strategy.

Before deciding whether to apply for a patent, it is important to understand how patents fit into your overall business strategy and which alternatives may exist. The sections below explain when patent protection can add value — and when other forms of intellectual property or different approaches may be more appropriate.

The main types of intellectual property

Intellectual property is commonly divided into two broad categories: copyright and industrial property rights. Each type protects a different aspect of creative or innovative work and plays a distinct role in a business strategy.

Copyright protects literary, artistic, and creative works such as texts, software code, music, images, and designs. A key feature of copyright is that it arises automatically at the moment a work is created. In most jurisdictions, no formal registration or application is required to obtain copyright protection. For a more detailed explanation, see our page on what is copyright.

Industrial property rights cover forms of intellectual property that are closely linked to commercial and technical innovation. These include patents (for technical inventions), trademarks (for brand names and logos), and industrial designs or design rights (for the appearance of products). Unlike copyright, most industrial property rights require a formal application and examination procedure before protection is granted.

Which type of intellectual property is most relevant depends on the nature of your invention, the stage of development, and the business strategy you pursue. In the following sections, we look more closely at how these different IP rights are used in practice and how they relate to bringing an invention to market.

Intellectual property rights and inventions

Within the broader framework of intellectual property rights, patents play a specific and well-defined role. A patent is a legal right granted by a government authority that gives the patent holder exclusive rights to commercially exploit a technical invention for a limited period of time.

This exclusivity is not automatic. The first step to patent an invention is by filing a patent application, usually done through a patent office or agency. The patent application is simply a set of documents written in a specific, prescribed format. Subsequently, it undergoes evaluation by an official government body, which may grant or reject the application based on whether it meets the legal requirements for patentability such as novelty, inventiveness, and industrial applicability. If granted, the patent allows its owner to prevent others from making, using, or selling the invention without permission.

The purpose of this system is not merely legal protection, but economic balance. After all, patents incur costs, right? However, a patent offers a crucial competitive advantage. Typically, developing an idea or a new technology into a mature innovative product requires a significant investment of money, energy, and time. Often, the inventor has devoted years of work and a considerable amount of (personal) funds. To ensure these costs are earned back and the results of all this effort aren't easily replicated by a competitor, a patent becomes an indispensable tool to protect your invention. Patent protection helps ensure that these investments can be recovered and that competitors cannot immediately replicate the result without bearing similar risks.

At the same time, not every idea qualifies as an invention, and not every invention requires a patent. Only when an idea is sufficiently developed into a concrete technical solution can it fall within the scope of patent law. In earlier stages, or depending on the business strategy, other forms of protection or contractual arrangements may be more appropriate.

A detailed discussion of when patent protection makes sense, how patent applications work, and how patents fit into different commercialization strategies is covered separately on our page about how to get a patent.

Choosing the right form of IP depends on your business strategy

Intellectual property is not a goal in itself. It is a strategic instrument. The type of IP protection that makes sense depends strongly on what you ultimately want to do with your invention.

Researchers and engineers often encounter intellectual property only after something “interesting” has been developed. At that point, the natural reflex is to ask: Should we file a patent? In reality, that question is incomplete. A more useful starting point is: How do I intend to create value from this invention?

Different commercialization strategies place very different demands on intellectual property. In some cases, patents are essential. In others, copyright, design protection, trade secrets, or even rapid publication may be the more effective choice. Making the wrong IP decision early on can limit your strategic freedom later.

On this website, we distinguish three main strategies for bringing an invention to market: Build to Sell, Sell an Idea, and Start, Grow and Scale. Each of these strategies relies on intellectual property in a different way.

For example, if your goal is to sell an invention or technology to an established company at an early stage, clear ownership of the core idea and a defensible IP position are critical. In contrast, if you intend to build a company around the invention and scale it over time, IP must support long-term market exclusivity, investment, and freedom to operate.

There are also situations in which formal IP protection is less important than speed, know-how, or reputation. Software, data-driven innovations, educational content, and creative works are often protected primarily through copyright or trade secrets rather than patents. In these cases, filing a patent may add cost and complexity without providing real strategic value.

The key message is simple: there is no “best” form of intellectual property in isolation. The right choice only becomes clear when IP is considered in the context of your business strategy, your role as an inventor, and the way you plan to collaborate with others.

The following pages explore how intellectual property fits into each of the three strategies in more detail, and how early IP decisions can either enable — or constrain — your future options.

When patents make sense — and when they don't

Patents are often seen as the default form of protection for inventions. In practice, they are a powerful but very specific instrument. Filing a patent application makes sense in some situations, and very little sense in others.

A patent is most valuable when an invention can be clearly defined in technical terms, is difficult to design around, and plays a central role in creating long-term commercial value. This is often the case for hardware innovations, manufacturing processes, medical technologies, or deep-tech inventions that require substantial investment to develop. In such cases, a patent can create market exclusivity, support fundraising, and protect the effort invested in research and development.

However, many inventions do not fit this profile. If an innovation evolves rapidly, depends heavily on tacit know-how, or can easily be implemented in multiple technical ways, a patent may offer limited real-world protection. In these situations, speed, secrecy, or contractual agreements can be more effective than formal patent rights.

There are also strategic reasons not to file a patent. Patent applications are published, which means that technical details become publicly available. This can be undesirable if the invention is better protected as a trade secret, or if early disclosure would weaken your competitive position. Cost, timing, and freedom to operate are additional factors that should always be weighed.

Importantly, deciding whether or not to apply for a patent should never be an isolated decision. It should be aligned with your overall business strategy, the way you intend to collaborate with others, and the role the invention plays within a broader portfolio of intellectual property.

A more detailed discussion of what patents are, how they work, and how to decide whether filing a patent application is the right step can be found on the page How to get a patent.

In research environments, patent decisions are often made late — or delegated entirely — which can lead to missed strategic opportunities. Technology transfer offices and IP departments tend to develop strong preferences based on their past successes and risk profiles. In my own experience, this meant that patenting efforts were heavily focused on pharmaceutical inventions, while medical device innovations received far less attention. As a result, several promising ideas were never seriously evaluated for protection, not because they lacked merit, but because they did not fit the existing IP mindset.

This is precisely why inventors and researchers should develop a basic understanding of intellectual property themselves. Even when IP decisions are formally delegated, being able to think strategically about protection options helps ensure that opportunities are at least recognized and discussed. You do not need to become a patent expert — but you do need enough insight to avoid leaving value on the table.

Focusing on patents alone can easily obscure the broader landscape of intellectual property. Many valuable inventions and creative outputs are protected — or leveraged — without ever filing a patent. Understanding the full range of IP options is therefore essential for making informed strategic choices.

Other forms of intellectual property beyond patents

Intellectual property extends well beyond patents. Depending on the nature of the work and the context in which it is created, other forms of protection may be more appropriate, more efficient, or more strategically useful.

Copyright protects original literary, artistic, and scientific works, including software code, academic texts, presentations, images, and documentation. Unlike patents, copyright arises automatically and does not require formal registration. For many researchers and developers, this form of IP plays a much larger role than is often recognized.

Industrial property also includes design rights, which protect the visual appearance of products, and trademarks, which protect names, logos, and other identifiers in the marketplace. In addition, confidential know-how and trade secrets can be protected through contractual agreements and internal controls rather than formal registration.

Each of these forms of IP serves a different purpose and comes with different costs, risks, and enforcement mechanisms. In many cases, effective protection involves a combination of multiple IP instruments rather than reliance on a single one.

The following sections introduce these forms of intellectual property in more detail and explain when they are most useful in practice.

Copyright and creative works

Copyright plays a central role in protecting written works, software, images, and other creative outputs that frequently arise in research and innovation environments.

A more detailed explanation can be found on the page What is copyright.

Confidentiality, NDAs, and collaboration

Before formal IP protection is in place, ideas and early-stage inventions are often shared with collaborators, companies, or investors. In these situations, confidentiality agreements play a crucial role in protecting ownership and preserving future options.

Non-disclosure agreements (NDAs) and material transfer agreements (MTAs) are commonly used to regulate what information can be shared, under which conditions, and with whom.

Read more about NDA's on the page Non-disclosure agreements

Enforcement, disputes, and risk

Intellectual property only has value if it can be enforced. In practice, this means understanding the risks of infringement, the limits of protection, and the mechanisms available when conflicts arise.

This includes issues such as patent infringement, licensing disputes, and formal litigation — topics that are often overlooked until problems arise, but which can have a major impact on commercial outcomes.

Intellectual property in practice: examples and cases

Real-world cases illustrate how intellectual property decisions can determine success or failure. Disputes, failed patents, unexpected rulings, and strategic mistakes all provide valuable lessons.

A selection of real examples and stories can be found in the IP news and case studies sections of this website.

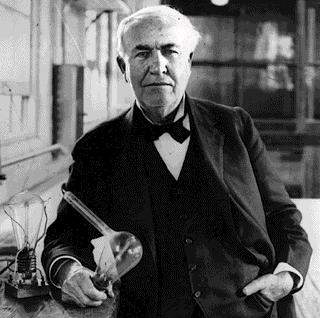

Thomas Edison: Inventor and Entrepreneur

In school, we learned that Thomas Edison is the inventor of the light bulb, but what the teacher didn't mention is

that he held nearly a world record in patents. He owned more than a thousand patents! However, not all of these were

his own inventions. Thomas Edison was primarily an entrepreneur who excelled in the game of making money through

patents. He bought many inventions directly from inventors and then applied for patents on them himself.

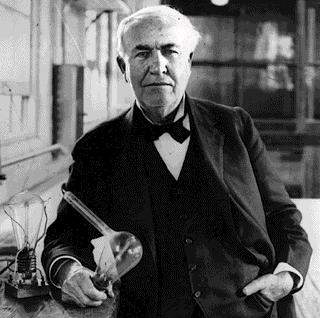

In school, we learned that Thomas Edison is the inventor of the light bulb, but what the teacher didn't mention is

that he held nearly a world record in patents. He owned more than a thousand patents! However, not all of these were

his own inventions. Thomas Edison was primarily an entrepreneur who excelled in the game of making money through

patents. He bought many inventions directly from inventors and then applied for patents on them himself.